UPDATE: This vulnerability has been assigned the Common Vulnerability and Exposure ID of CVE-2018-7698 by MITRE.

I’ve been testing out a beta version of an IDS (Intrusion Detection Sensor) that we’re planning to release sometime soon specifically for small businesses, tech savvy home users, and others. I currently have it running on my home network and the alerts I’ve been seeing have really made me much more aware of the potential risks we encounter every day. For example, a game my wife plays on her mobile phone has been triggering spyware and malware alerts thanks to the ads that constantly pop up.

One of the more interesting alerts I’ve seen came from the security cameras I have been using, and it’s even more evidence to support the concept that we should be using unique passwords for every system.

For the last year I’ve been using a set of D-Link security cameras to watch my house. My wife loves them because she can snoop on the dog while we’re at work, and I enjoy the peace of mind that comes from knowing that I didn’t leave the garage door open. Again.

I picked them for two reasons: they were cheap and well reviewed on Amazon.com. The specific unit I ordered was the D-Link DCS-933L with a list price of around $30 each, currently running firmware version 1.05.04. The biggest selling point for me was the convenience of being able to access the cameras from anywhere in the world using a website or app and without needing to punch any holes in my home firewall.

That said, I wasn’t born yesterday. Devices such as these, whether you call them “embedded devices” or “internet of things (IoT)” devices, are notorious for being massive flaming dumpster fires in terms of security. Routers are an obvious “soft target” as WikiLeaks has shown, but more specifically the FTC actually filed a lawsuit against D-Link for the terrible security implementation in some wireless routers and cameras. I wasn’t taking any chances so when I set up my network I configured a completely separate router segregated from everything else on my network where I connected the cameras, isolating them and therefore limiting the damage they could do should they be compromised.

I had protected myself from the devices, but I didn’t expect that the “secure” app would be telling everyone on the internet my password.

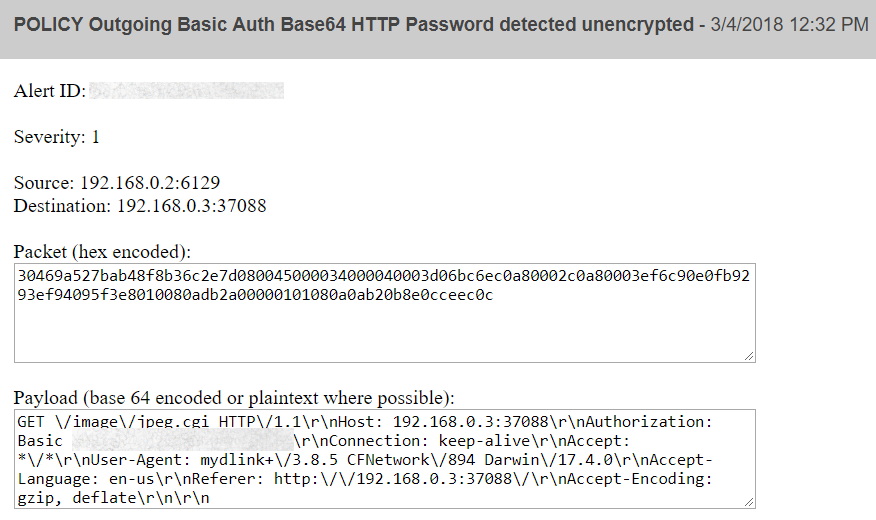

This was the first alert I received through the beta IDS dashboard I’ve been working on. This came in shortly after my wife had opened the mydlink app and used it to view one of the cameras. That text in the payload which is blurred is the username “admin” and my password for the device sent encoded as a base 64 string — so trivial to decode that WireShark does it automatically.

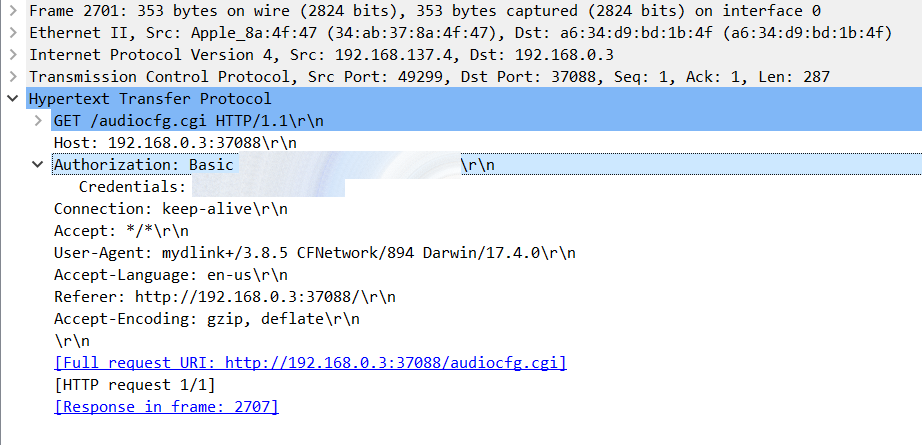

Naturally I was curious about what was going on, so I fired up a quick packet capture and replicated what happened. Turns out that yes, my password for the camera is being sent unencrypted over the internet every time I log into the camera.

Here’s how things work, as best as I can tell:

- When the camera is registered with the mydlink website the user is asked to supply the camera’s password. I was hoping that this password would be used to generate an access key of some sort but apparently it is simply stored in a database.

- When a user logs into the website and selects a camera, the username and password combination is sent to the app in an encrypted stream using SSL (just like the rest of the data from the site).

- The app then supplies the username and password over an unencrypted HTTP session directly to the camera which opens an unencrypted HTTP stream containing the raw video content.

All of the communication between the app and the website itself is encrypted using SSL, but the communication directly between the app and the camera is completely unencrypted and contains the username and password for the camera itself.

According to the D-Link manual for this camera, this functionality is not described. The local access functionality is described in detail, where you can expose a web server running on the camera directly to the internet and connect from anywhere in the world, but that’s pretty much the insecure configuration that caused the FTC to file a lawsuit against D-Link.

What’s concerning is that this password is sent in the clear. For anyone listening in on the connection (for example, on an open WiFi access point) it would be trivially easy to grab that password and use it for their own nefarious purposes.

This might give a malicious actor the ability to log into your camera remotely, change the settings on the device, and watch the stream without your knowledge.

In situations where that same password is used in other applications (such as banking websites or other applications) a malicious actor could potentially identify your username simply by watching over your shoulder and use the password to log into your accounts.

In short, nothing good could come of this. Thanks, D-Link.

What this illustrated to me more than anything else is the need for an Intrusion Detection Sensor (IDS). No matter how secure applications claim to be or how security minded the employees, things happen. Malware is constantly evolving and trying to make it into your environment, and with the proliferation of mobile devices and Internet of Things (IoT) devices where traditional antivirus applications aren’t an option a good IDS or other monitoring system is more essential than ever.